How do you get HPV?

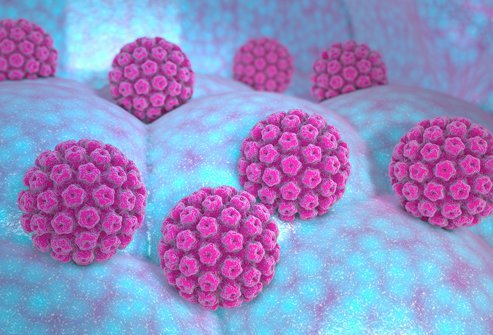

Human papillomavirus, or HPV for short, is a common type of viral infection. While HPV doesn’t come back after clearing completely, it’s difficult to know if an infection has actually been resolved or is simply dormant.

Human papillomavirus, or HPV for short, is a common type of viral infection. There are more than 100 types of HPV, and many infections are asymptomatic — you can be infected without even knowing that you’ve contracted HPV.

While most HPV infections disappear on their own within a few years, some cases linger in the body and can cause different health problems like genital warts or certain types of cancer. While HPV doesn’t come back after clearing completely, it’s difficult to know if an infection has actually been resolved or is simply dormant.

Additionally, while you’re unlikely to be reinfected with the exact same type of HPV, you can be infected with another strain.

Many types of warts, including common warts, plantar warts, and genital warts, are caused by HPV infections in the top layers of skin.

As a result, HPV is spread primarily through skin-to-skin contact. Warts are highly contagious and can be passed from person to person or by touching something that a person with a wart touched.

Genital HPV is sexually transmitted through oral, anal, or vaginal sex, as well as close skin-to-skin contact. Infected people can spread HPV even if they have no symptoms, and most sexually active people will contract HPV at some point in their lives.

Is HPV dangerous?

HPV can be asymptomatic and resolve on its own, but some types of HPV can lead to cancer.

HPV is divided into “low-risk” and “high-risk” strains. Low-risk strains can cause warts on the fingers, face, hands, or feet. Low-risk HPV causes types of genital warts that don’t typically lead to cancer.

High-risk HPV can lead to cancers involving the genitals or oropharyngeal cancers — i.e., cancers involving the mouth, tongue, and throat. More than 90% of cervical cancers are caused by HPV.

How is HPV diagnosed?

There’s no general test that can tell you if you have HPV. If you have warts, though, your doctor may be able to diagnose HPV through a visual exam. If you have symptoms of genital warts like genital itching or burning, but your doctor doesn’t see any warts, they may perform a vinegar solution test. HPV-infected areas turn white when a vinegar solution is applied, making it easier for your doctor to detect small or flat warts.

If you have certain types of high-risk HPV that may cause cervical cancer, it can be picked up by a pap test designed to look for abnormalities in the cells of your cervix or a DNA test performed on cells from your cervix that can detect the DNA of high-risk types of HPV.

How is HPV treated?

HPV treatment depends on what type of HPV you have and what symptoms you’re experiencing. You can often treat common warts at home with over-the-counter salicylic acid.

If you have facial warts, genital warts, or warts that aren’t responding to over-the-counter treatment, your dermatologist may recommend another type of wart removal. Possibilities include:

- Prescription creams

- Trichloroacetic acid

- Freezing warts off with liquid nitrogen

- Burning warts off with an electrical current

- Cantharidin — a toxin that causes a blister to form under the wart

- Cutting out the wart

- Laser treatment

- Immunotherapy — treatments that encourage your immune system to fight off the wart

If high-risk HPV is detected in your cervix during a pap test or DNA test, your doctor may want to perform a biopsy of any areas of the cervix that look abnormal. If you have precancerous spots that need removal, your doctor may recommend a procedure such as:

- Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) — removal of a thin layer of the cervix with an electrically charged looped wire

- Cold-knife conization — a surgical procedure that removes a cone-shaped piece of the cervix

- Freezing of abnormal cells

- Laser treatment

Is HPV preventable?

You can prevent some strains of HPV with vaccines. All 3 HPV vaccines licensed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration protect against HPV types 16 and 18, which cause most HPV-related cancers. The HPV vaccine can prevent most cases of cervical cancer, as well as other genital cancers, oropharyngeal cancers, and genital warts.

The vaccine is only effective if administered before you’ve been exposed to HPV. Consequently, the CDC recommends that all children be vaccinated against HPV at ages 11 to 12, as well as all adults under 26 who didn’t receive the vaccine in childhood. It may not be as beneficial for adults over the age of 26.

If you’re over 26 and unvaccinated for HPV, talk to your doctor about whether or not the HPV vaccine might help protect you. While most adults over 26 have already been exposed to some form of HPV, vaccination may help protect you from additional high-risk strains.

If you haven’t been vaccinated against HPV, you can reduce your risk of cervical cancer by:

- Using a condom during sexual activity

- Getting regular pap tests starting at age 21

- Quitting smoking

While HPV is common, high-risk strains can lead to serious health consequences down the road. Vaccination is the best way to prevent HPV-related cancers.

If you haven’t been vaccinated, talk to your doctor about the potential risks and benefits of an HPV vaccine. Your doctor will be able to answer your questions about your individual risk of HPV-related cancers.

If you have persistent warts or warts on your face or genitals, call your primary care provider or dermatologist to determine the best course of action.

SLIDESHOW

12 Preventable STDs: Pictures, Symptoms, Diagnosis, Treatment See Slideshow

Medically Reviewed on 5/31/2022

References

Sources: American Academy of Dermatology Association: “WARTS: DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT.”

Centers for Disease Control: “Cancers Caused by HPV,” “Genital HPV Infection – Fact Sheet,” “Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination: What Everyone Should Know.”

KidsHealth: “Warts.”

Mayo Clinic: “HPV infection,” “HPV vaccine: Who needs it, how it works.”

NYU Langone Health: “Types of Human Papillomavirus.”